by Stuart Urback

Coming into 2020 I assumed that one of my preferred social activities — tabletop games — would be pretty insulated from any societal catastrophe, given its small footprint and lack of electrical requirement. Yikes was that wrong. The legacy game I had been playing with friends was put on hold. What happened was an experience in pragmatism. I focused on games that brought my closer together with friends, digitally. I played more digital board games this year than any year previous: starting with Istanbul over my birthday, Jackbox with coworkers in April and May, and Fall Guys, Root, and Scythe closer to the end of the year. The pandemic forced me to stop and reflect on what I wanted from games instead of chasing a new mechanic.

I spent a lot more time watching movies, especially mainstream ones. I watched the Mission Impossible series, most of the Ghibli films, and rewatched Avatar: the Last Airbender. Content that was easy to consume became helpful because my attention span decreased dramatically from the stress and the stress of dealing with a new living situation. Large, sprawling games that I was already disinclined to play became unapproachable, and medium length titles that I could schedule time for became distant.

At the same time, I felt like I should accomplish so much more, now that I wasn’t bound by all these social obligations. That didn’t pan out. While I might have had more time, adjusting to a new reality at work and home and trying to drag myself away from the news left little effort towards personal achievement. But the reflection, and the new perspective, gave me an opportunity to rethink how I thought about the world and what sort of media I value. The conclusion I came to is: I hadn’t given enough direct feedback, I overvalued big progress and undervalued iterative change, and that my personal perspective was too informed by defensiveness and not by opportunity.

I’d like to think my favorite games this year reflect that. They probably don’t. But, as the author of this piece, I get to define the types of games I enjoy and then explain why the games I pick fit that. The theme that I felt most notable from all of these games is how they forced me to rethink how I thought about the world and spent time with other people. The other main criteria I used was playing enough of something to have an interesting opinion. Games like Last Campfire and A Monster’s Expedition have a beautiful art style and got me to start playing, but I hadn’t gone far enough to feel they impacted my year. It is a bit of a high bar to clear but deeper understandings feel like a core theme. This kept another Apple Arcade title Crossy Castle off my list. It’s a snappy implementation of a platformer (I appreciated that it was playable in portrait mode on my phone), but it stayed within well worn territory that experiences like Super Mario have already led.

The games I picked are ones that shaped the way I thought about the world in 2020, that uniquely responded to the demands of my life, and that represent directions for design and publishing that I hope to see more of in the future.

Honorable Mention

I want to call out five games that didn’t hit every note, but are worth taking a look at. I might talk about them more in the future

They’re either games that I felt I would never put in the top-5, but wanted to call out for their impact, or games that I felt were this close to being a game of the year for me, except for a lack of a play time, or a couple of small disconnects.

Tussie Mussie was a re-introduction to the tiny game format that Button Shy games develops, where rules for a game made up of 18 cards fits into a wallet sized containers. That it happens to be a drafting theme and by one of the most famous board game designers of the last 5 years didn’t hurt either.

World Next Door was one of the first games I played this year. It’s an interesting take on the “Match-3” genre (Bejeweled, Candy Crush) that expanded the themes into a narrative format rather than leaning into the procedural “high score” goals that are typical of the genre.

The Solitaire Conspiracy is a late entry by Bithell games, in their shorts line. The shorts line is cheaper, smaller games that put a high level of polish on games that are playable in 5 or so hours. It’s an interesting take on solitaire where the face cards have powers, but sometimes those powers hurt you instead of help you. The twist for face cards to have special powers was an energizing change, but I found myself avoiding all of the “negative” specials. This made me feel like I was able to avoid a decent chunk of the game.

Before We Leave is an inviting take on the civ-building genre. The art style feels similar to Pixar, with big round worlds built up of hexagonal tiles. I appreciated that the interface options which helped me maintain control and focus (a typical reason I give up on the civ genre rather quickly). I dropped it because it required a bit more time than I could give but I look forward to picking it back up in 2020.

For the King is the closest thing to a popcorn game on this list, but as a tactical strategy game, I appreciated that the exploration was exciting, and the fights were quick. One of my biggest frustration with most tactics games (like Pokémon) is that fights can drag on, and strategy depth is just confusing enough to require more time than I’m willing to put in. It delivered a pleasurable, if unchallenging experience.

5. Fall Guys

Certain games are games you can carry a conversation while enjoying. In baseball vernacular, it’s what you’d call a pastime. Falls Guys is a pastime for me. It’s a game where you control a bean character/person through an obstacle course (think Wipeout meets American Ninja Warrior). Starting with 60 competitors, you either race to the finish or try to be the last one(s) standing. Each level waves of opponents are eliminated until only 1 player remains.

Mechanically, it feels almost possible to play Fall Guys with only two commands: move and jump. Before I figured out the controls I was mostly limited to those anyway. There are some occasions where you’re have to dive or cling to a wall, though those come up less frequently. Its simplicity means it’s easy to learn, but there are enough moves that you can develop skill while you play. Dan, my frequent playing collaborator is much more adept with controls so he often makes it into later rounds while I failed early and often.

Even when losing, Fall Guys is a fun game to spectate and play with friends. It’s easy enough to have idle conversations while the game is ongoing. Playing the game meant staying in touch and forming new, fun memories while talking about how our weeks went.

I would like to see more battle royale games with concepts outside of shooting. This is where the success of games like Fortnite has a positive impact on the overall industry. Because Epic, the makes of Fortnite, also own Unreal Engine (a premier game engine), many of the toolsets used to create royale games have become accessible to teams with fewer resources. But Fall Guys simplicity masks design complexity that isn’t obvious to see. Games that might be fun in person can drag or feel unfair against an anonymous (if adorable) hoard of enemies. Finding an engaging combination of speed, multi-player elimination, and skill seems like a fun area for future games to explore.

Playing over the summer, when online games were the main ways I interacted with friends, Fall Guys presented a genuine way for me to connect. It's complex and active enough to be engaging but not so complex as to become a game of silent intensity, without discussion or chatter.

4. Wavelength

In a pandemic-free world, Wavelength might have been my game of the year. It was the first game I brought with me to a company retreat. I played it again a month later at a going away party. Each time it brought hilarity and insight. It was a game that held up even though we would play for hours each time.

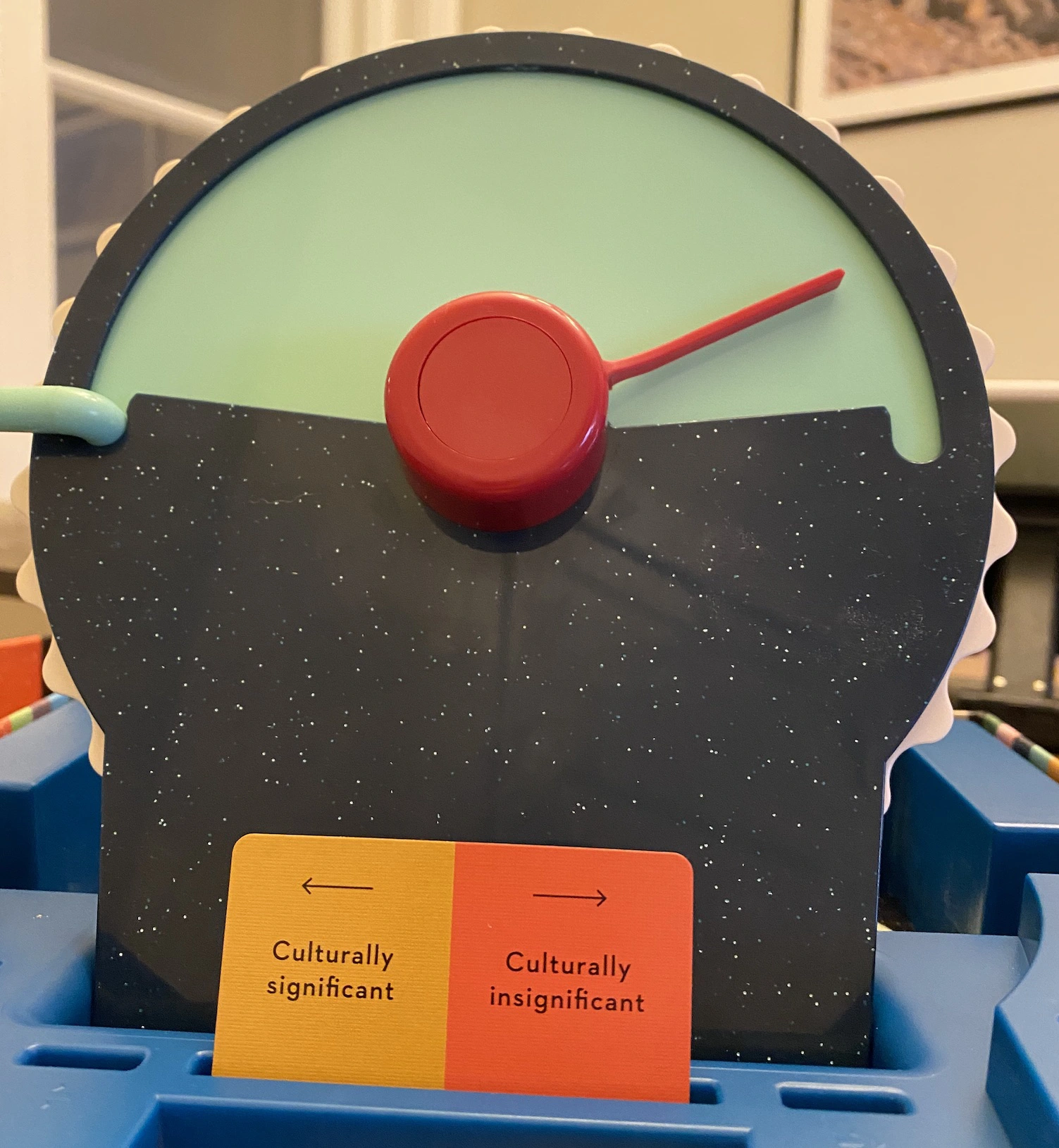

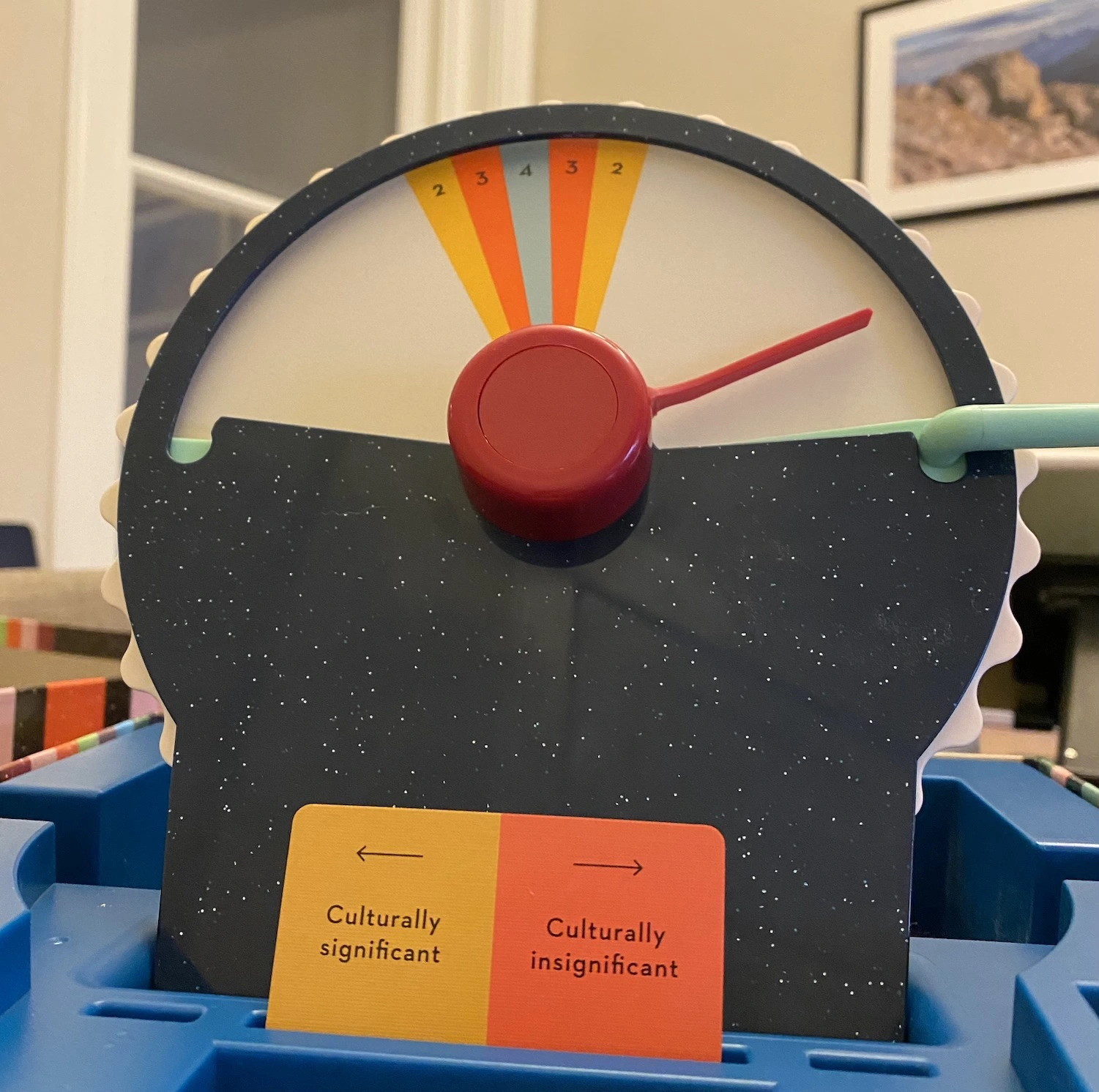

For a party game, Wavelength is surprisingly hard to explain. It has a similar structure as Charades where one player knows a secret (in this case the location on a dial). Everyone gets to see the words representing either end of that spectrum (let’s say hot on one end, cold on the other). Then the clue-giver has to give a single concept (without explaining themselves), that will get their team to turn the dial toward the right spot.

This might be easy if the secret is towards one end or the other. You might say sauna, if it’s on the hot side, or igloo if it’s on the cold side. But what if it’s on the 60% hot. What do you say then? You might say “lukewarm coffee” but will players think that’s actually 60% cold, instead? The uncertainty leads to deep conversations about how players see the world, and the reveal at the end of the round ends with drama as the screen is flipped back to show whether guessers were wrong or right.

The other thing that surprised me about Wavelength was how often we’d ditch the rules and play collaboratively, taking turns trying to get the group to guess, rather than competing in teams. I usually dislike “conversation starter” type games immensely, because I think they’re feeble attempts at faking social interaction without a lot of support from the “game” in terms of how that’s supposed to happen. Wavelength is the right amount of structure (it’s clear what the clue-giver is supposed to do, and what the clue-guessers are supposed to do), with uncertainty (who knows what anyone else is thinking) to bring excitement and insight.

3. Good Sudoku

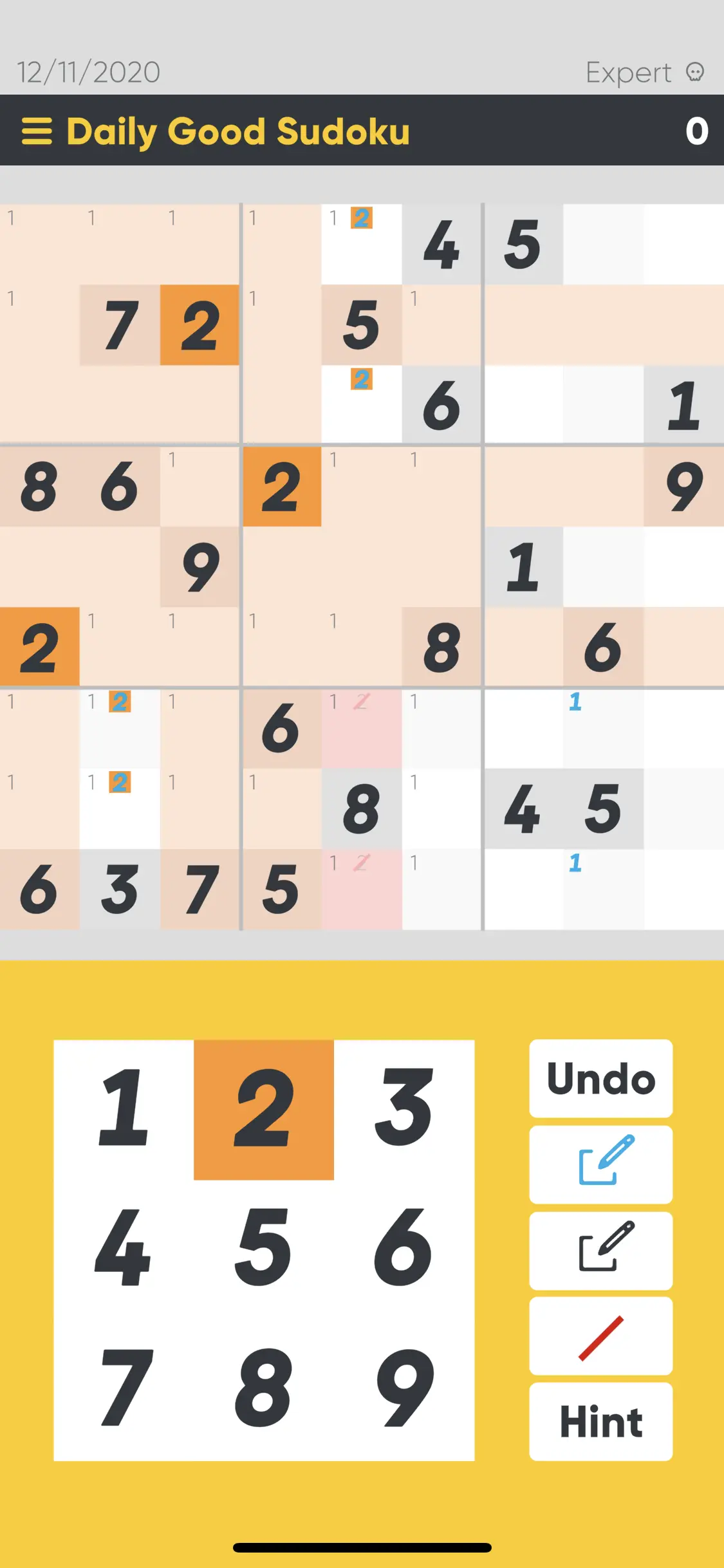

Good Sudoku almost didn’t make the list. It’s a re-imagining of Sudoku by Zach Gage and Jack Schlesinger. It contains a lot of UI and UX tweaks that make it easier to see some of the core concepts of Sudoku. At the bottom of the screen there is a number pad and some notation options. The notation options allow you to mark, highlight, or cross out numbers on the grid. If you tap on a number by itself, it will shade the other areas of the board, illuminating patterns more easily.

I’ve had an off-and-on relationship with this game. When it was released over the summer I played it non-stop. The combination of new notation system, haptic feedback when it auto-filled a space, and the bright colors made me feel fast while playing the game. It’s take on teaching the rules helped me learn new concepts and got me excited about a world of Sudoku puzzles I hadn’t thought of before.

As a design enthusiast, I found it exciting because it felt like a different experience without changing the rules of the game. It opened up a concept to how different UI and feedback transform a player’s experience. I also appreciated that they had daily challenges, and that those challenges use the same system that the New York Times Crossword uses (each day Monday to Sunday gets harder).

I gave up the game after I felt like I’d hit a wall. I knew all of the somewhat nuanced problem solving techniques, but was struggling to see anything new. That’s when I realized that I was playing games for time rather than the enjoyment of solving the puzzle. It felt rote because I could go through all my techniques but would get stuck and was unsure how to think creatively. I came back to it this month, and still find myself enjoying the daily challenges but sticking away from the other formats. It’s fun for a 5-10 minute puzzle.

Calling this game “flawed genuis” feels a bit over the top, but that’s where I’m at with it. The concepts it introduces change the game of Sudoku to feel more electric and high-powered. They also push Sudoku into a different experience with the puzzle that feels slightly more formulaic and less free. It reminds me of the relationship between becoming an expert and being blind to a beginner’s mindset. Good Sudoku is incredible because it gives you all of the possibilities of being an expert, off the bat, but it also locks you into that expert way of thinking, without necessarily developing it on your own.

For the moments when I felt stressed and trapped, when I wanted anything else to think about, it was there with a puzzle, and helping hand to solve it. I appreciate the energy and the concepts so much that it overcomes the flaws but it might be the type of game that you enjoy for a few days and put down, rather than the one that you build into your life. I’ll keep it around because I wonder if there’s maybe an update that’ll unlock that next level for me to push, advance, and get faster at solving puzzles.

2. Lonely Mountains: Downhill

I wrote an entire review of this, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Lonely Mountains made it almost to the peak, as it were. It’s a great game. Go read the review. Listening to podcasts while playing this game became an important part of my daily routine for a few months. The game gave me the opportunity to develop a skill, riding down the mountain. It did so through precise feedback that helped me learn and grow in its systems while my brain pondered and turned thoughts over. The game’s rigorous implementation of feedback created an immersive experience.

But I realized that anything I took away from the game would be the result of my own actions. As Ian Bogost says in Shit Crayons, humans are capable of spinning endless situations into positives, but it doesn’t make the situations themselves any better. It would be easy to read this as a critique of Lonely Mountains, that I believe the game would be better if it had tried to find a mirror for me to look at. That’s not my intent. The technical brilliance in Lonely Mountains is meditative rather than transformative. In 2020 I looked for something more. I looked to a game that tried to imagine a better world.

The opinions in this post are expressly the views of the author and do not reflect the views of their employer(s) or any entities that they might otherwise be affiliated.