by Stuart Urback

In Dicey Dungeons you play as one of six heroes who have been turned into dice by an evil game show host, Lady Luck. You battle your way through a game show in order to earn your escape, or so you think. The game is cheerful and cartoonish, with bright colors, big, graphic characters, and snappy one liners. The aesthetic persists through the game mechanics, which are based around equipment you collect and the dice you “roll” to activate them.

Dicey Dungeons has a deceptively simple design. Each turn you roll dice and use them to activate equipment, damaging your enemies. Some equipment deal damage based on the number of pips on the dice, others require even/odd numbers on the dice, and apply status effects. There is a clear cause and effect between the equipment you use and the damage you deal to each enemy which made Dicey Dungeons easy for me to pick up. This initially led me to assume that the design under the hood was equally straightforward, but as the designer Terry Cavanaugh detailed in a blog post, there’s a lot of complex work going on just beneath the surface. This is a consistent theme in the game, rule complexity is hidden so that the player can feel the flow.

The challenge of the game comes from picking the combination of equipment to battle with. Players will find some equipment in chests which they can get to after defeating monsters, some will be found in “carts” either in exchange for money or for other equipment they own. Getting these decisions right feels like the key to winning the game: pick the wrong equipment and even the best rolls won’t save you.

The Delight of The Dice

Where other games hide the math behind damage calculation, Dicey builds the entire game around showing players how damage is calculated. Character health levels are counted in the 10s (except for the final boss), and most attack values are between 1 and 6, the values found on the dice you roll. The transparency makes the game feel more approachable than other rogue likes. You don’t have to spend a lot of time figuring out what the underlying system is doing, and the system is simple enough that you can reason about it in your head.

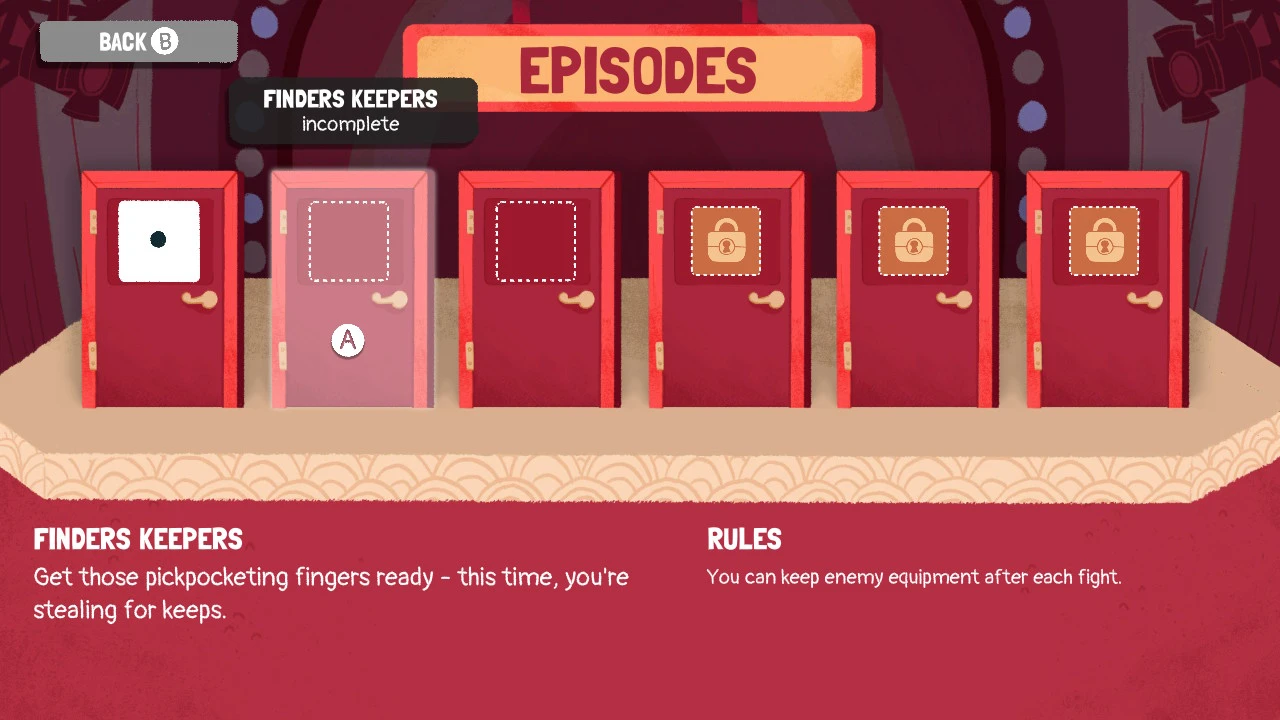

For many rogue likes the procedure of the world is designed and then players combine objects to exploit and create new possibilities no one imagined. Dicey Dungeons feels more deterministic and more authored than other rogue-like games. While the pathways are semi-random and the equipment you will find is randomized, there are a set number of levels you can reach, and certain classes of characters that you will meet on each floor. The “combo potential” of equipment interaction is limited by the number of dice you roll per turn. While this might limit the depth of the game, it also means there’s fewer unknowns to catch you by surprise, making the game overall feel more approachable. Instead, fun is unlocking new content and seeing what tweaks and twists the designer has laid out for the player. The tweaks and variations behind each door are the heart of the game’s depth.

Gentle Exploration

Part of the fun of playing a rogue-like is in building an understanding of how the world works. For example, in Spelunky HD you could try to steal something from the shop-keeper only to learn that the shopkeeper will try to run you down and kill you if you do. This form of exploration is fun, it encourages players to try stuff out, but also can hide a lot of the depth of games from players who don’t think of experiments to try. I’ve found confronting many different axes of uncertainty to be a barrier to my enjoyment of these games. By narrowing the types of exploration, Dicey Dungeons left me more free to fully explore the combinations the equipment and player powers have to offer.

Dicey Dungeons simplifies exploration by focusing on a discrete set of variables: how the different equipment interact with the dice roles and player powers to create strategy. The run lengths are short, so it’s easy to try out a set of equipment and then learn why they don’t work, only to immediately restart. And the reward for leveling is an increased number of dice, which means that as a run continues it’s more likely that your equipment will do what you want. This creates a tight feedback loop where a player tries to see how different pieces of equipment work together, loses quickly for negative feedback, or is rewards by getting to do more of the same thing they already enjoyed.

The reward structure also sets up a clever inversion during the harder levels (doors 4-6). Rather than only increasing your rewards, the game will start making it harder on you as you go further, potentially by adding tricky rules or by reducing your health as you gain levels. By this point though, I felt comfortable enough with the character, having a deep understanding of the equipment I preferred, to overcome the challenges the game threw at me, which increased my feelings of success. This is where the authored approach truly shined, it felt like the game had built me up by giving me support as I learned the character, and then turned the game upside down on me right when I was ready for a deeper challenge. I felt successful the whole way through.

The Long and the Short of It

The downside to this authored approach is that when I get stuck on a level, the challenges can feel arbitrary and painful. I found myself wondering if forcing the player to go through so many different concepts (battling with each character at least once, and winning with one character at least 6 times) create a barrier to the types of exploration that Dicey Dungeons tries to encourage? Completing a single round of Dicey Dungeons_is simple (about 30-40) minutes, but completing the entire game is an investment. This is the biggest barrier to the game, and it’s possible to imagine that it could dissuade some people from playing the game altogether. Terry Cavanaugh, the designer, even contemplated as much on twitter. He said he felt like _Dicey Dungeons is too long. In short, there’s a lot of game to get through, to get to the content. For a game that’s otherwise so approachable, the time investment to get satisfying results could be a turnoff.

I prefer Dicey Dungeons to most other roguelikes because the time to complete a single “run” (the level or campaign in the game) is 30 minutes, instead of the more typical hour or so. Compare this to Slay the Spire, one of the gold standards of the genre, where a successful run can take an hour or more. But in order to understand where Dicey Dungeons trips it’s important to talk about the motivations that games set-up their players with in playing. Film Crit Hulk, a popular film (and sometimes game) critic, has a good heuristic for different types of games. He groups them into roughly one of two categories: “flow” games, like Assassin’s Creed and “learning” games, like Slay the Spire. In flow games, the goal is to successfully engage the player while delivering content and mastery at well timed intervals to make the player feel and improve in line the content they’re delivering (often in this case story beats). Learning games are more about the system itself, playing is a means to deeper understanding of the system.

Dicey Dungeons lives somewhere in the middle of the two. Dicey Dungeons is a learning game in the sense that you are trying to learn how to work well with each character in order to complete a run. It is likely that you will fail as you learn which equipment work best, and which upgrades to use. As you fail you will get better at making decisions for each character. But it’s also a flow game in the sense that each new character is an exciting piece of content, and each piece of content is not so complex to operate that there’s a lot of excitement to fully exploring the possibilities of operating them. I found most of the excitement was in being given a new concept or idea to play with, rather than in a deeper understanding I got from thinking about the rules of the game in a new way.

Flow games can trip over themselves when story becomes locked behind challenges that require repetition to overcome. I believe the main reason for this is the overjustification effect. Overjustification is the concept that external rewards reduce intrinsic motivation to complete tasks. In this example, narrative (the game show) or content (new characters or challenges) are the external rewards and the joy of playing a mechanic is the internal motivation. Flow games often rely on the designers to fine tune those moments where players might get stuck and offer them a helping hand. This might come in the form of (sticking 5 shovels around an island to make sure you find 1 in the case of A Short Hike), or taking control of the camera to point the player directly at the thing they need to see. But a learning game like Dice Dungeons doesn’t have this same control because the designer can’t “know” at any moment where the player might be.

When Dicey Dungeons is successful the hybrid of the two feels exhilarating. Winning a run after 3-5 attempts has all the exhilaration of a learning game, because I figured out the right combination of equipment and strategies to win, and also because I know I’m getting a new character, new challenge, new equipment to experiment with. The combination feels like a burst of energy. But it can start to feel like a slog when I’m torn between wanting to know what happens next but also need to focus on learning about the game so I can beat it. And because the mechanics are more authored, I felt less like I’m missing some underlying mathematical concept, and more like the arbitrary way a particular level was designed hurts. I found myself wishing the path to unlocking the story were easier, so I could spend more time picking the game up to explore new concepts rather than being driven by a desire to unlock the final character or the end of the game. It’s hard to focus on the joy of a single run when there’s a payoff waiting (the final boss) that you know you have to get to.

Games like Super Mario Odyssey have managed this by reducing the requirement to unlock new levels or new story to a small percent of the total content of the game and then designing the areas so that the players want to come back for more. I think Dicey Dungeons is a strong enough game to have done the same, and I found myself wondering why I needed to beat every character 6 times to unlock the final boss. I would’ve happily continued playing through unlocked levels even after, because the novelty of each new experience was so inviting. But after grinding through the game in 2019, I was so exhausted that it wasn’t until it came out for the Switch that I picked it back up. There’s nothing wrong with a player deciding to put down a game before it’s done, and even if you played each character once, I would still recommend this game. But games should also afford players to end at their pace without making them feel like they’re breaking the logic or the narrative of the game.

Unequivocally: You Should Try It

I still happily completed every level in Dicey Dungeons, and I picked the game up again when it came out on Switch because it brought me joy. Given that I tend to drop most games before experiencing more than half the content (the aforementioned Slay the Spire and Super Mario: Odyssey come to mind here), completing all of the challenges and defeating the boss represents an achievement for me. And it wasn’t because I felt like I had to, to experience the story: the game brought me novelty, excitement, and learning each time I played. There’s something inspiring to play through the results of a game designer experimenting with multiple different ways to twist and tweak a simple concepts: dice rolling. The love put into the design is easy to see as you play the game. The game also has a vibrant modification culture which the designer supports and encourages. Due to the restrictions of consoles, modifications are only accessible on PC, but if you have the PC variant I’d encourage you try to out the MegaQuest if you’re looking for more to play. Dicey Dungeons continues to feel like an exciting and welcoming possibility space that I expect to play off and on for quite some time.

The opinions in this post are expressly the views of the author and do not reflect the views of their employer(s) or any entities that they might otherwise be affiliated.