by Stuart Urback

Food Chain Island

Food Chain Island, published by Button Shy games, is a solitaire game in their series of wallet-sized games. All games in the series come in the same container, a plastic wallet. It’s an interesting concept that’s attracted quite a few big names in the design space. This game, designed by Scott Almes (creator of the Tiny... series) is an solitaire contribution to the Button Shy series.

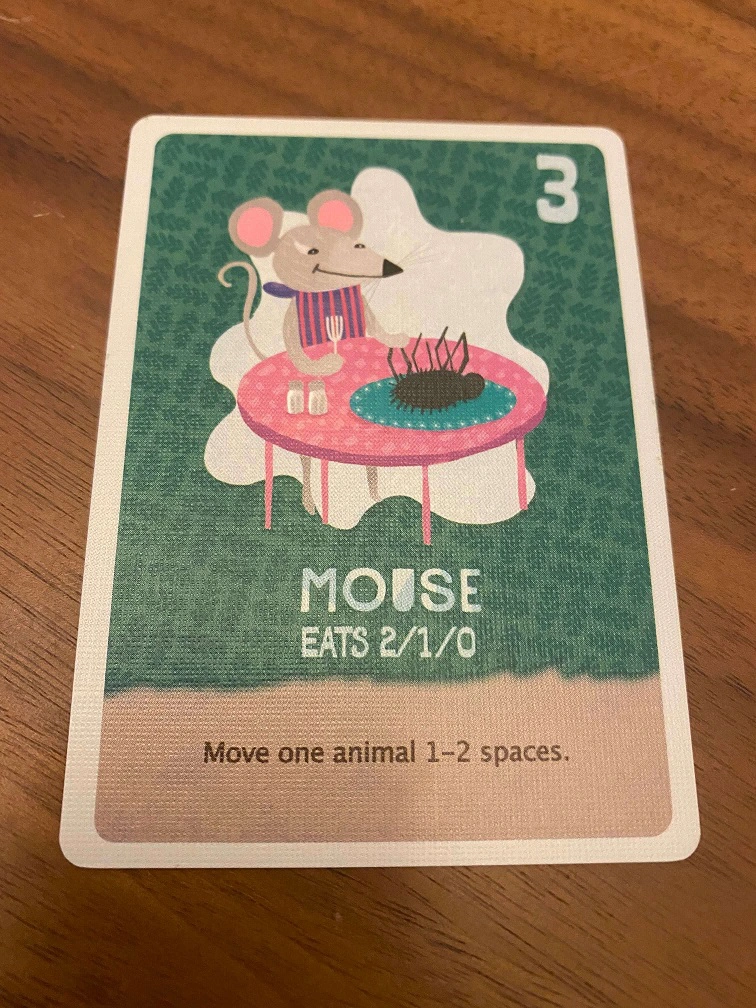

The game consists of dealing all 16 cards (numbered 0 to 15) into a 4x4 grid, face up. The goal of the game is for the player to get the laid out cards from 16 individual piles into 3 or fewer stacks. The rules are simple. Each turn the player stacks cards with larger numbers on top of adjacent cards with smaller numbers. The game calls this eating. But there’s a twist, cards may only eat cards that are up to 3 smaller than them. This means a 12 can eat a 11, 10 or 9, but not an 8 or smaller. This restriction turns the obvious “most to least” strategy into a careful set of steps to puzzle over. There’s one more twist to help and challenge players. Each card has a special ability which must activate after a card eats.

Solitaire v. Single Player

Single player games are in the middle of a renaissance. It started a couple of years ago, but has picked up in popularity as the pandemic wears on. Because war games have no hidden information they’ve been some of the first games to feature solo modes. Economic games, with indirect competition, often have single player variants. Players in these try to score a high score rather than out-score an opponent. But the smaller sub-genre, solitaire games, has seen less exploration. At first I hesitated to differentiate solitaire and solo games. I thought solitaire (or solitary) was another way of describing a single person playing a game. I learned that solitaire describes stacking and arranging a deck of shuffle cards. The distinction between solo games and solitaire games, therefor, seems important.

Solo games, especially modern ones, contain interlocking systems. Solitaire games has a single system which governs arranging cards. A solo variant of Wingspan (a popular birding board game) has resources like eggs, food, and bird cards which restrict and inform the player’s actions. Food Chain Island has a single system, the cards in the 4x4 grid. These cards both restrict and provide the player with opportunity. Solitaire designs have to be more economical with their resources. At the same time, my expectations for the game are smaller. I’m not looking for a set-up, building tension, or a payoff. Instead, I look for a single question which presents new opportunities with each shuffle. For Food Chain Island the question is, “how can you stack the cards from a 4x4 grid into a single pile?”.

Solitary Innovation

Algorithmic exploration feels like a domain owned by computers. Food Chain Island proves this isn’t the case. It uses the stacking mechanism and shuffle to hide and open up new possibilities with each play. It feels like there has been an explosion of takes on solitaire in the digital space. In the last five years games like Solitaire Conspiracy, Flip Flop Solitaire, and Ancient Enemy have come out. But there hasn’t been the same investigation by prominent indie designers in the physical world. I think this has to do with the constraints of each medium. Because of Microsoft Windows, lots of people have experience playing solitaire on their computers. And computers can introduce opportunities to tweak the format. This includes adding a story, special powers, or different combinations of suits/colors. In the physical world, competition is fiercer. Solitaire games have to contend with shelf presence and component costs. This is where concept of wallet games works to the solitaire format’s advantage. 18 cards that fit in the size of a wallet evokes a feeling of ease and portability.

That’s what makes the innovation of Food Chain Island so enjoyable. The stacking mechanic is useful in two different ways. First, because cards get covered up as they get “eaten” the complexity of the game decreases over time. Second, it creates a tension in losing the ability to use a power as it’s covered up.Really wanted the bat’s swap ability? Well I guess you can’t eat it with the snake then. Maybe next time.

Two of my favorite sequences are what I call “the pile-on” and “the checkers” maneuver. The “pile on” involves a stack surrounded by four other cards. The sequence of numbers means that you are able to eat the center card with each of the surrounding ones. This leaves one remaining. The “checkers” maneuver involves taking a single card and eating three smaller cards. Both are satisfying because they are hard to pull off and also eliminate many piles from the board.

The other challenge solitaire games have is their direct competition with digital games. Playing alone means competing against a phone game, a computer game, a Nintendo Switch game, or even twitter. Because Food Chain Island is only 16 cards to shuffle and deal it’s easy to start a game. The lack of friction brings it to the table when other more involved games might stay on the shelf.

Permission To Cheat?

One part of Food Chain Island tripped me up, the sea creatures. These are two ”extra” cards which you can discard to shift cards on the 4x4 grid into better positions. They end up as sort of “get out of jail free” cards to escape board states where you’re stuck. At first I felt like these were an unnecessary addition, a cheat tacked onto the game.

After playing with them for a while I realized that they solved a core problem of puzzle games. When you play Klondike solitaire and get stuck the solution is to shuffle and start over. This isn’t terrible, but becomes a rough experience if it happens often. Sea creatures create an outlet to push players beyond stuck points. This in turn allows more experimentation and learning about the game. This got me thinking about permission structures in single player games.

When I play solo games I notice that I will often give myself leeway to “bend” the rules. Often this means interpreting the rules of a card in the most generous possible way. However I won‘t allow myself to rearrange the board at will, that feels like cheating. If I’ve gotten into a situation where I can’t use a generous reading of the rules to get out, that’s it the game’s over. How and where we’re stretch the rules is anachronistic but often rather inflexible. That inflexibility can present problems for game designers trying to create enjoyable games. A common example I imagine is a crossword puzzle that’s abandoned because a puzzler can’t find the right word. That person might have been able to solve the rest of the puzzle, but that gap became a sticking point. The sea creatures give permission to break the flow of the game without feeling like failure.

Even though the sea creatures feel discordant, (sea creatures helping land creatures eat one another, really?) they serve a larger structure to help the player progress their skill in the game. As I continued to play the game, I noticed myself playing with the sea creatures less and less. I had gotten better at the game. These affordances feel like an exciting area for game designers to play with. How can we create training wheels that players can choose when they put on and take off?

There’s a World to Explore

Manipulating physical cards adds a delightful tactile sensation to the entire experience that great digital solitaire experiences can’t compare to. Food Chain Island is a refreshing game to play and think about. The thing that strikes me most is how it makes the concept of card based solitaire feel really open for exploration. There’s an expansion with air creatures coming out early this year and I can’t wait to see where it goes next.

The opinions in this post are expressly the views of the author and do not reflect the views of their employer(s) or any entities that they might otherwise be affiliated.