by Stuart Urback

Introduction

On my bookshelf in the bottom row, right in the middle, there's a dusty, dog-eared copy of Carcassonne, the first niche board game I purchased. I’ve recycled or donated many of the games I bought early on, but Carcassonne holds a special place in my collection. It’s simple but creates dynamic and cool city scapes as you play the game. Until recently, I hadn’t found any similar computer game that filled a similar niche.

The concept of building and managing the various elements of a city has been popular since SimCity came out in the 1980s. City building games are, as the name suggests, about growing and maintaining cities. Games in the genre focus on the social, economic, and political systems that keep cities running and often don’t have a goal. They can be a playground for your mind to run wild with the possibilities. But the lack of direction and the complexity of the systems stressed me out, so I stayed away. Recently, there have been a couple of new games that have me re-examining my previous assumptions about city builders. Games like Islanders, Dorfromantik, and Townscaper offer a different take on the genre that add structure and reduce the systems to the bare minimum. Like Carcassonne, they take the complexity of city building and abstract many of the economic and human systems into a simple set of points, counted up as you place tiles.

What is a City Building Game?

The fiction of a city builder game is one of persistent growth. The player plays the role of city planner and omniscient being to fill in the space of a grid with buildings and roads for the citizens to inhabit. The fun of a city builder is watching your city grow in size and dealing with he challenges that creep up. As noted in Why Medieval City Building Games are Inaccurate this conception of how cities grow, especially in medieval times is inaccurate. Cities were barely subsistence between the 12th and 18th century so growth was a distant dream. And even today, US cities haven’t grown much in the last decade. City growth becomes an excuse to make the interesting decisions and to tend to the different elements of the game. When you sit down to play a city building game, the growth and expansion are the tools the game uses to give you interesting options.

The components of the game then are growth, handling minutiae, and making intelligent decisions about how to place the buildings and roads to ensure your city grows. What’s unique about city building games is your current decisions constrain your future ones and you end up in a success or failure of your own making, though there are outside forces that can lay waste to well-laid plans. The tension in a city building games comes from how the player spends their money, and the way they manage the minutiae of the relationships between the different types of buildings. To take a simple example, putting housing next to an industrial building will make the citizens unhappy because of the pollution.

While the more famous games of the genre like SimCity or Anno do this with various complex systems, other games accomplish similar goals with less complexity.

How Many Systems Does a Game Need?

One of the challenges to complex economic systems is that they can fail to give the player immediate feedback. A decision you made early in your city (like where you happen to put roads) can be hard to undo, without you having a clear understanding of why. This is even problem in another stripped down “city building” game Mini Motorways has. You get trapped and can’t find a way back out, which is a pretty disheartening experience. Games like Islanders, Dorfromantik, and Townscaper go the other direction., they’ve stripped the systems out of the game and focused on the placement and the building.

In each of these games (maybe Townscaper excepted) the tension is in how close you want certain tiles to sit together, and how far apart you want others. These games share a focus on placement. Each “turn” you place a single tile onto the board. In the case of Islanders, it’s a building on an island, in Dorfromantik it’s a tile onto a hexagonal grid, and in Townscaper it’s a colorful element on the misshapen grid.

Removing so many elements of the simulation changes the focus of the game on the physical space they take up. The aesthetics are important beyond their ability to mimic a “real” city. They create a unique perspective on the (abstract) ways cities can look and exist.

Islanders

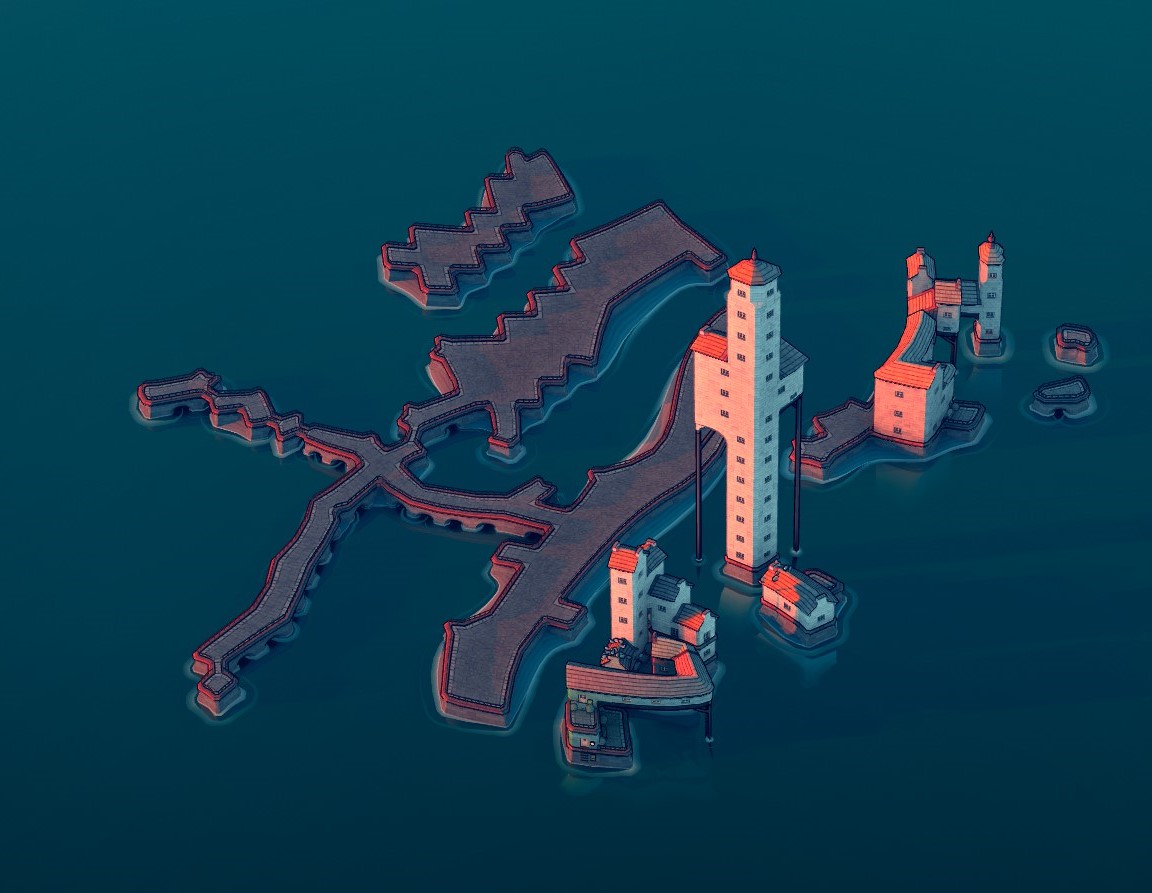

Islanders by Grizzly Games came out in 2019. It shrinks the city building to the small space of an island. Instead of a big sprawl, the game asks players to position buildings islands in different configurations to score points and continue building more buildings.

Each level players get a set of buildings to place across the island, scoring points based on their relationships to the other buildings in the area. A house might get bonus points for being placed next to the shaman or the city center, but the shaman will get fewer points placed next to the city center. These combinations create a tension between where you players want to set their buildings. They have to pay attention to location now and potential future locations to set themselves up for success.

The goal is to use the buildings in each round to score enough points to get to the next round and then get another new set of buildings. The game ends either when the player chooses to move to another island, or when they placed all their buildings but haven’t scored enough points for the next set.

The layout of the islands got me thinking about the physicality of the city I was building. Instead of a grid or a wonky grid, I had freedom to spread out all the different locations, but I had to pay a lot of attention to the location of each piece. The minutiae of Islanders is caring intensely about the location of each. As the island got more crowded I zoomed in and out, rotating the island and the building, to find the best possible place to put it, hoping that I could nudge it just close enough to another building to get a couple more points.

Dorfromantik

Dorfromantik is a tile laying city building game. You start with a deck of 50 tiles. Each turn you have to place a tile to match different segments (including rivers, railroads, fields, forests, and houses) with one another, similar to Carcassonne. Some types, like rivers have to be connected to one another, so placing a new tile creates a restriction for where the next tile can be placed. Some tiles also have a goal associated with them, some number of consecutive tiles that need to be placed together to “complete” that objective. If you complete the objective, you get more tiles added to your deck and the game keeps going. Similar to Islanders you’re trying to make combinations to push your score higher to keep playing.

Unlike the other games, compactness is the focus of Dorfromantik. Because there are so few tiles (and few ways to replenish them) you want to maximize the number of different connections you can make with a given tile. When I started playing the game, I focused and matching similar tiles to one another, but I quickly created a sprawl and ran out of tiles before I could complete my next objective. These relational restrictions are a trope of city building games. You want to keep similar tiles close, but also want enough variety to make sure you don’t cause problems for yourself in other ways. One of the fun aha moments for me was figuring out that it’s smarter to sometimes place tiles one or two spaces away from an immediate connection, so that you can set up an even better connection in the future.

As the game goes on, the goal numbers get higher and higher, more houses to connect more trees to put into a forest. But it also throws a wrench in your plans. Rather than having all the objectives be a number or greater some tiles will be an exact number. So after you’ve put together a field of 50 consecutive tiles, you’ll be asked to set a goal of a field with exactly 10, forcing you to find a new space to start over. It’s this kind of variation that makes the game fun to play over and over.

Over time the game will spiral out of your control. Each tile you place will take you further away from your goals as you watch your deck dwindle. But the result is a beautiful map with giant forests and fields, interspersed with railways and rivers and housing developments. If I had to pick a favorite, it would be Dorfromantik.

Townscaper

Unlike the other two games Townscaper appears to be a toy at first glance. There aren’t any apparent rules or goals guiding your behavior: no points or end states in sight. There’s a pallet on the left side of the screen with some colors of the houses you can select, and a highlighter that follows your mouse around the screen.

The “play” in the game comes from the grid that gets generated and the way the building tiles appear. It exemplifies how, as A Game Design Vocabulary explains, a game’s opinions aren’t the goals it sets, but the tools it gives you to shape your experiences. Townscaper shapes your play by giving you few configuration options. The grid is a wobbly hexagonal (ish) shape and all you can do is click to add a house, or right click to destroy. But the shapes you can end up creating are spectacular.

Townscaper also gives you another key piece of freedom neither Islanders nor Dorfromantik provide. In each of those games you’re stuck at a 3/4s bird's-eye view, allowed to rotate and zoom in and out, but stuck at an angle. In Townscaper you can move the camera however you want, and even zoom way in or way out. Framing your city becomes part of the fun of the game. The game even gives you tools to change the lighting by time of day and direction. It gives you the tools to tell the story you want and then backs out of the way. It’s hard not to build a cute city and imagine yourself strolling through it on a quiet evening.

For Townscaper the story is the one that the photo you’re creating tells, rather than the one that the game’s rules provide you. It shapes your experience with nudges rather than an explicit goal, but the outcome is more interesting than it would be otherwise. If you check out the townscaper hashtag on Twitter you’ll see an incredible array of designs and ideas. If you’re looking for a relaxing game where you can paint your way to a gorgeous town, Townscaper is the one for you.

The Lego of It All

Playing these games led me to realize that one of the joys of the city builder genre the excitement of seeing a city and getting to place yourself in it. Each of the games, whether with an overt structure or a more gentle one created a landscape that I could imagine myself ambling my way around. It reminded me of playing with Lego and telling stories about the cities and the characters within them.

Each game is also a lesson in how algorithms that appear random can shape our behavior. The cadence and appearance of certain types of tiles in Dorfromantik, like how the “train station lake” rarely appears, changes my strategy and makes me avoid combinations of railway and river tiles next to one another. And in Islanders which options appear during each level up shape the type of town I’ll build on my island. And in Townscaper the lack of a strict grid creates interesting shapes and opportunities for experimentation, forcing my brain out of basic patterns.

Each game shows how a concept like city building can be distilled to a couple of basic forms and then expressed in a variety of ways with different opinions and goals. Islanders is a game about exploring the physicality of the space, Dorfromantik is about the relationship between different types of tiles and Townscaper is about using lighting, color, and framing to produce visual art. If you have 20 minutes and find yourself wanting to get lost in a miniature world, you should check out any of these games.

The opinions in this post are expressly the views of the author and do not reflect the views of their employer(s) or any entities that they might otherwise be affiliated.